Among the Honored Dead of Quang Tri

Por: Bruce Weigl

I don’t have any time to waste, so I’m going to say this thing as straight as I can. I have always believed in the power of stories to take us away, to lift us from the mundane, and deliver us to the powerful forces of the imagination, where anything is possible; later in my writing life, I learned too about the power of stories to save us. This is one of those stories.

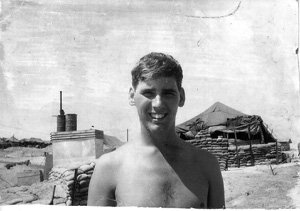

December 1967, I found myself an eighteen-year-old boy who didn’t hate anyone, no matter what my bayonet training had tried to teach me in our basic military training to become soldiers to fight in the American War in Vietnam. I want to give you all of the specific and necessary details so that I can take you back to that time and try to make you feel like you’re standing there beside me as I tell you this story. The truth is, I don’t remember much about my long transit to the Ton Su Nhut airport near Saigon back then, and then gradually north where I ended up at or near a basecamp 30 kilometers or so north of the city of Hue on Highway Number One, and on a few LZs called Betty, Jane, Sharon and up near the DMZ, LZ Stud, established by the 1st Air Cavalry for its assault on Khe Kanh to relieve the Marines who were under siege there by what we were told were as many as fifty-five thousand North Vietnamese Regular Army soldiers. The buzz was, and the battalion commander himself said in one of those pre-battle pep talks, that there would be many loses on both sides. This was something you were supposed to accept without question, for the honor of your country. I moved through that landscape gradually over a few months, and in the fog of war, in the dusty haze of uncertainty and fear and loss, I was somehow transported from one place to the next where I did what I was told and didn’t even think enough to remember some things I should have remembered.

These were lonely and scary places to me that I never felt safe in and was always glad to leave. I always felt surrounded there, in the dark on guard duty, by some quiet and powerful force that could come and swallow me whole into the night without a sound and without anyone being the wiser.

The great machinations of the war moved all around me in ways that were inexplicable to me, impossible to understand, because sometimes you can be so close to a thing, even inside of it, that your vision is blurred and all that you see is a life, day to day, a way of surviving that seems on many occasions impossible to survive.

In December 2010, thanks to the efforts and planning of my friend and co-translator Nguyen Phan Que Mai, I came back to Quang Tri, and to Hue and to Dong Ha. I came back as part of a book tour for my recently published collection of poems and essays translated by Que Mai called Sau Mua Thoi Na Dan, and with the poet Que Mai, to deliver over seven hundred books to the disadvantaged children at the wonderful Thuan Thanh Primary school in Hue. This is the same school that has received support from the William Joiner Center and Kevin Bowen in the past. These books were donated by the Women’s Publishing House, with additional books being purchased with prize money that Que Mai won for a variety of poetry prizes in 2010.

Delivering those books was one of the great days of my life. The dharma teaches that making other people happy is the greatest joy in the world, and seeing the faces of the special needs students at the Thuan Thanh Primary School, lit up with what can only be called joy of the most innocent kind, at the beautifully wrapped boxes of books that Phan Que Mai, I learned later, had stayed up into the night to wrap, was more than worth the long journey it took us to get there, and my life felt as full as it ever had.

Later, I also had the chance to kick a soccer ball around a dusty courtyard in front of the school with some boys and a few girls, and above the children’s’ laughter to see an old man play soccer, I thought I could hear the artillery pound away at the nearby mountains as they had those so many years ago when people were forced to live in the Vinh Moc tunnels where several babies had been born into the darkness and where many grew up. This is something my country did to people we didn’t even know we could love, but the sound was only thunder, rumbling from somewhere very far away, but very close too.

When Quang Tri City finally fell to the liberating forces in early April of 1972, the first most important victory for the North Vietnamese Army as well as National Liberation Forces, who eventually set up a government there, I was an undergraduate student at one of the most prestigious undergraduate colleges in the US. I was privileged to be a student there; I had no money, and the costs to attend the college were way above my or my family’s means, but the school believed in me and took a chance, supporting me for over three years with scholarship money. I was comfortable in my life there, and grateful for the opportunity, although the war raged on in the background, and always in my mind, where I could too easily imagine men and women still falling into their own blood.

I was walking through that life one day, through a cafeteria on my way to a part-time dishwashing job, and I noticed that a group of students and staff had gathered around a small television, watching some kind of news program. I stopped to watch too. A somber cloud hung over the group of young Americans. Uninformed, they saw the fall of Quang Tri City to the Communist forces as a bad thing, an unfortunate thing that would only lead to more, and more serious problems for the people of Vietnam. People believed this because in the 1960s, Americans still believed that their government always told the truth, and always did the right thing in the name of justice; this is the song and dance they’d been selling to the American people throughout the long war years. When I realized what I was watching on the television, I shouted out a joyful and loud Yes, and pumped my fist in the air in celebration of this important victory. It had been a long and hard-fought battle – several battles really – where far too many Vietnamese and Americans had lost their lives. I didn’t know then that the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, with the support of the US Army, dropped more than 80,000 tons of ordinance, with the destructive power of almost six Hiroshima-size atom bombs that would kill and cripple even more people. By May 1st, however, all of Quang Tri was in the hands of the revolutionary soldiers. All of this I learned only long after the facts. My version of the history of this time is tempered by the very narrow lens of an eighteen-year-old soldier, far enough away from home so that he may as well be on another planet, and caught up in the great wheel of history, like it or not.

At the back of my mind during the entire trip, the Truong Son cemetery had waited like a silent presence in the dark, just out of sight. I knew that we would eventually get there, thanks to the planning of Que Mai, but I also felt anxious for the first time about going, about being in what was hallowed ground for the Vietnamese; their own particular national cemetery, where not too long-ago Americans were not even permitted to tread. I wondered what right I had to be among the spirits of these brave men and women, if I had any right at all, and I wondered what small thing I could do or say there in that magnificent presence.

The writer and Deputy Head of the Quang Tri Writers Association, Cao Hanh, along with the journalist Le Duc Duc, invited me to visit the cemetery with them, and with Phan Que Mai. On the way, Cao Hanh asked me questions about where I had fought, and where I had spent time as a soldier in the war in 1968. When I told him that I’d been around the Dong Ha, Quang Tri, Hue area, he told me that I must have certainly fought against his brother who had been at the same places at the same times, fighting against the 1st Air Cavalry. We laughed about the coincidence and about how small the world really is. I felt the car come to a halt and looked up to see the entrance to the cemetery. As soon as I stepped out of the car I felt a powerful urge to walk immediately among the gravestones, so I trusted my instincts. I no longer felt like an alien, but like someone who belonged, and was welcomed.

Located on a lonely hill surrounded by eight other hills in a pattern that some people say looks like the petals of the eight-petal flowers that grow in the Vinh Truong Commune nearby, the main part of the cemetery includes ten thousand two hundred and sixty-three tombs of fallen soldiers. “The Memorial of the Nation to Soldiers’ Sacrifices” sits on the biggest hill. The cemetery is a resting place for the soldiers who fell fighting the Americans on the Ho Chi Minh trail, where some of the bloodiest and most sustained close fighting took place.

Standing in the center of the cemetery among my friends who had brought me here, and among the remains of over ten thousand North Vietnamese and Revolutionary Force soldiers, lost in the many battles for Quang Tri City and the Citadel, lost in battles I had directly or indirectly participated in and had been attacked by these same soldiers, all of the facts seemed to drift away into meaninglessness. When so many are lost, or made to suffer, there is finally no way to count; there are no numbers to contain what it means to lose your life, or your family, or your future to an invader’s war.

The afternoon was hot for December, especially for me, who had come from freezing temperatures to eighty degrees in the sun. Away from the shade of some nearby banyan trees, out among the grave markers in the sun, I’m sweating but from more than the heat I begin to realize. I can hear some children laughing and playing nearby, and some insects chirring in the trees, otherwise it is very quiet. I stop for a moment by one of the grave markers. I read the name and dates. I move to another marker, and then another; I move up and down the rows and across almost frantic in my impossible wish to pray at them all. My friends have faded somehow into the distance it seems, and my head is spinning a bit from what I thought must have been the heat, but I move down another row, and then another, reading the names and dates, and sometimes the places where they had died. I walk in the sun and try to pay my homage to the spirits there who called something out, I’m sure, when I offered up some incense to the honor of their memory and to their bravery expressed solely for their country and for their fellow citizens, in the face of enormous odds in the form of a literal storm of bombs.

* * *

It had been forty two years since I’d stepped into harm’s way in and around Quang Tri City, Dong Ha, and Hue, but for the first time ever, I could begin to feel the full weight of those I’d fought against who had died and were now buried here, below my feet, like me, struggling under the hot sun with no breeze and no bird song. I could finally begin to feel the full weight of their sacrifices, and of the long suffering of their families, some of whom come here regularly to remember and honor their war dead. I never had the opportunity to speak with any of these men or women those many years ago when we were enemies because of the stupid facts of history, and for a long time after the war, it was impossible for me to even travel here, to the beautiful cemetery called Truong Son, but if I had spoken to them then, I would have found a way to say I grieved their loss twice in my life: once as an eighteen year old soldier in a great army destined to fail who in spite of all the odds, knew something was wrong with what his country was doing to Vietnam and the Vietnamese people, and once again today, standing among my friends, who have found me in the darkness I had wandered into, and who light incense now beside me at another grave marker, all of us, offering a smoky path back to the world, and our love.

Oberlin, Ohio

February, 2020